With the Maasai!

No 5-star safari lodge. No suite with beds and mini-bar. No wide-screen satellite TV.

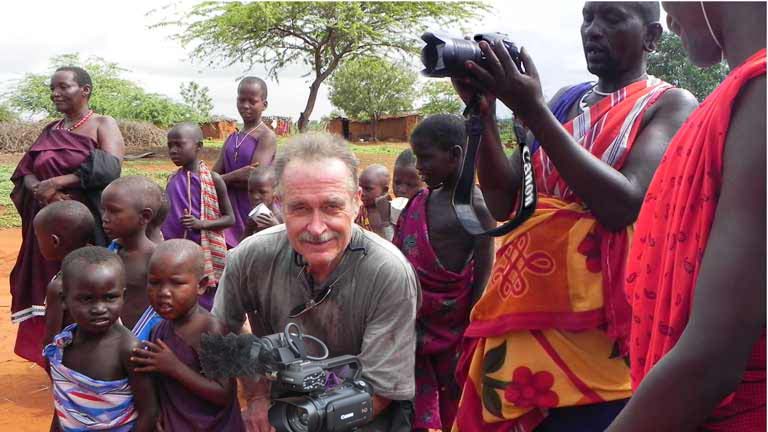

Above, an image from a Maasai village 2 hours west by bus from Mombasa. My friend from the township, Nelson Kiguni, took me there.

As an NGO field operative, he had worked with Maasai throughout Kenya. He respected their traditions. Yet he recognized the desperate poverty of their villages. He asked me, "What can we do?"

I asked them of their work.

Cattle. Sheep. Goats.

What of the safari parks? Foreigners come here to see the exotic animals. Do they come here also?

Trucks come for us. We dance for the foreigners.

How much do they pay?

Nelson talked with them. He finally told me, "Almost nothing. Tips. The foreigners take photos, they pay the Maasai to stand with them and they take photos. Videos. And they give them some money. Almost nothing."

Photos? Videos?

I traveled there with three cameras. When they saw I had more than one camera, my XA10, they asked to use the others. The Maasai share everything. I shared with them. They did very well, following instructions, composing images, pressing the right buttons. An ideal came to me. Click on the video: