Kenya! With thanks to Ethiopian Airlines!

No 5-star safari lodges. No tours in Landcruisers.

In Kenya, I stayed in townships and villages. Above, an image from M'hango Kayole Junction, the entry road to M'hango.

I stayed with a family in this township, M'hango, an hour by bus on the Eastern Bypass highway from Nairobi. Beyond fast food restaurants of this junction, the road crosses what were green fields cut by the Nairobi River. Shop stalls line the sides of the road. On the sidelanes, the walled homes of Nairobi professionals show the beginnings of a suburb. At the river, where hunters once killed cocodiles for meat, egrets and migratory birds appear from time to time. M'hango is a chaos of estates, grazing cattle, and individual enterprise.

Below, a short video shows the main street at dawn, as a young man cooks and sells street-kitchen donuts called, Mandazi.

Township Micro-Enterprise

Kenya offers few opportunities for the youth of the townships surrounding Nairobi.

Without tools, without education, they can only hope for ditch-digging or construction day-labor. Or they can try for day to day work in Nairobi. But that requires bus-fare and hours on the jammed roads -- if they find work.

This video shows morning in Mihang'o, an hour outside of Nairobi.

( Note the aircraft passing overhead in the video. M'hango borders the international airport. Only the highway and police firing range divides the township from the transnational corporations of Jomo Kenyatta International Airport. All that wealth, within bicycle distance of Mihang'o. )

The young man in this scene had access to an empty storefront -- and a padlock to secure his business.

In the empty shop, he kept the tools of his business: a table, mixing bowls, a knife, a fry pan, a long handled spoon. The materials: cooking oil and flour. And with those tools and materials, he made mandazi, the small wedges of dough oil-fried and sold the mandazi one-by-one.

5 Shillings. 5 U.S. cents. ( At that time, $1 equalled 100 Shillings. )

I first approached to buy, camera down, hanging on my sling. When I asked the price, he told me 25 cents. He laughed. Everyone laughed.

I knew the real price. Throughout my time in M'hango, when I could not walk due to wounds, I had given children shillings for our breakfast food. Bananas, bread, yogurt, fruit juice, mandazi.

And he knew I knew the real price. Everyone in the township knew the family with whom I lived. And he knew that the children came to his stove every morning and bought sacks of mandazi for the American and the family. Bags of mandazi. He knew the wounded American to be a big-time customer.

So, when everyone laughed at 25 shillings, I laughed. And I made a deal.

I'd buy ten if I could video.

Okay.

And here's the video. Cost me 50 Shillings.

There are young men and women throughout the townships without tools. Without skills. Schools cost money. Training costs money. For families without steady work, they cannot risk hunger to send their children to schools and training courses.

And tools? Impossible. Electric tools? Electric tools require electricity.

Consider this: Al Shabab, the Al Qaida gang murdering thousands of Somalis and Kenyans, offers $100 US per month to carry a Kalashnikov.

The young man in this video made a future with himself with a few tools and a lock on an empty shopfront.

And as he worked in the dirt and smoke of M'hango, the private aircraft of the elite and the airlines of the rich foreigners passed overhead.

Backstory:

Why stay in M'hango when I could go anywhere in Kenya?

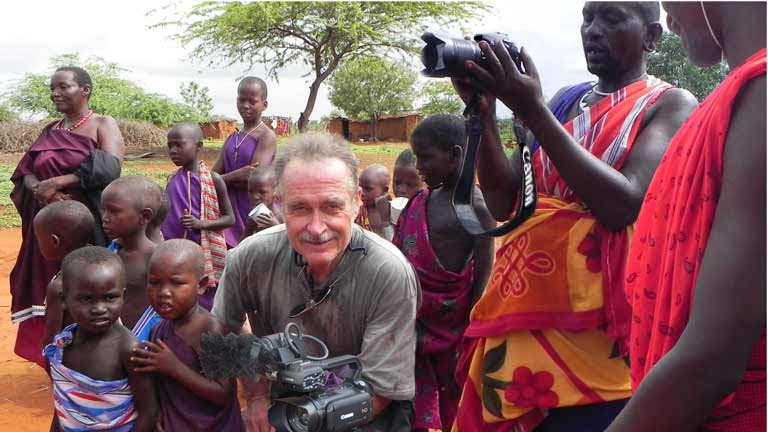

I had intended to travel to the Tsalvo acacia forests to continue my MaasaiCameraMen project with the with the fellows there. Here is the video showing the start of that project in 2013 and 2014:

I had intended to travel to the Tsalvo acacia forests to continue my MaasaiCameraMen project with the with the fellows there. Here is the video showing the start of that project in 2013 and 2014: